by Kirby Laney, posted 9 April 2018

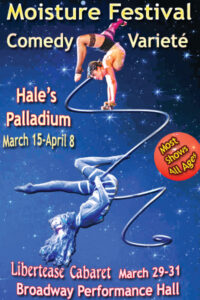

In 2018, the Moisture Festival gave its all for its 15th year, and marked a major triumph for the vaudeville & burlesque showcase. Around the world, others have attempted to produce similar shows, but Moisture Festival is the largest and longest running operating today. Fifteen years is a long time to manage 40 shows, featuring over 100 artists, produced nearly all by volunteer effort to sold out houses almost every performance.

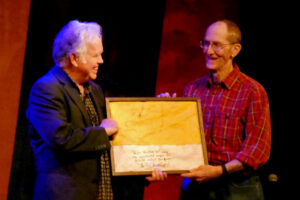

On April 2nd, at one of the free, educational Tent Talks that are also on the Moisture Festival calendar, videographer Alan Plotkin produced a rather elaborate panel discussion. Over the course of three hours, twenty of the people who inspired, founded, and continue to organize Moisture Festival, talked about what makes it all possible. Moderated by John Boylan, at Hale’s Palladium, this impressive crowd paraded on and off the stage, deftly demonstrating how making Moisture is a super-human effort.

The Inspiration & Antecedents

Tom Noddy started the discussion by explaining a bit of vaudeville history. According to him, “vaudeville died in America in the 1930s,” and nearly died in Europe. “Hollywood drew all the headliners and talent,” and killed live entertainment. “You could see them on Ed Sullivan,” he explained.

In the 1970s, street performing became the place for these acts to reach an audience. Reverend Chumleigh shared stories about how performers sacrificed, like Robert Shields, a mime who risked arrest to perform in public, “until the courts gave up,” and laws changed. Tim Furst explained how the Oregon Country Fair, begun in 1969, gave these performers stages, and audiences a place to see them. They made no money, and camped in the dirt, but they built up followings and names – and connected with others doing similar work.

For bubble-blower Tom Noddy, performing outside, in the weather, didn’t work so well. However, he met the Flying Karamazov Brothers, who introduced him to cabaret work, as it was called in San Francisco. In the Pacific Northwest, they called it vaudeville. According to Furst, “they had a whole other scene in the Northeast; in Maine and Vermont.” Yet, there too performers had begun building shows and schools, in small enclaves, to come together and share.

The same appears to have been happening in Europe, where performers had more options, but not many more – even in families sometimes four or five generations in circus. German clown Hacki Ginda had been touring Europe, but after the wall came down, he gathered people together to perform variété shows in his home of Berlin. “I’d found out that before the war there were 220 theaters in Berlin,” he recalled, yet The Chameleon, which he began with four others, was the first variété theater in Berlin since World War II. “It was really successful,” Ginda said, staging 9 shows a week for 14 years.

Tom Noddy recalled meeting Ginda when he attended The Chameleon’s late-night ‘Miternachtshow’, during a tour in Europe. Ron Bailey also remembers meeting Ginda at the Oregon County Fair (OCF,) but the three really date their friendship from when Noddy invited Ron to join him (Noddy’s girlfriend couldn’t go,) at a Variety Festival Ginda produced all around Berlin, and at his theater.

The Beginning Of Moisture

Ron Bailey enjoyed the two tents, store front and theater venues that Hacki Ginda had enlisted as venues for the Berlin festival, and the talent he’d drawn – jugglers from Africa, performers from Australia and Japan, and a bubble blower from America. “To have all these performers together,” Bailey remarked, “the hanging out among the performers is what led to Moisture Festival. It taught us the value of these shows.”

Maque daVis knew Bailey, through OCF and his variété troupe, Royal Famille du Caniveaux. daVis had his own troupe, Cirque de Flambé, a fire circus, that the Fire Marshall had begun to extinguish, and he’d begun working with Simon Neale on what would become the Fremont Players. When Bailey told daVis about his festival vision, and a suggestion about an OCF in Seattle, the idea inspired him.

Tim Furst also knew Bailey from OCF, and daVis from Cirque, and he had been looking for, “a place for performers to gather.” A member of the famous Karamozov Brothers, Furst knew 100s of performers, many of them friends, who he wanted to be able to work with again, in his neighborhood. “To make it a place where performers want to come,” he explained about the vague idea, “money would be less important. The place and the food would be much more…”

Bailey enlisted them, along with Neale. Bailey praised Neale’s “energy and positivity to the venture.” They found Sandy Palmer (like Neale, she couldn’t attend the April 2nd presentation,) who daVis described as, “our PR person, who would go out and talk people into anything!” Bailey explained, “Sandy was a worker bee. So were Maque and Tim!”

Together the five produced the first show, with Neale and Bailey dreaming big, and drawing in other volunteers. The Producers selected a U-Park Systems lot in Fremont where they erected a tent rented from Reverend Chumleigh. They scoured Fremont, and Seattle, soliciting assistance and donations. One they got easily was kegs from Hale’s Ales.

As the story goes, when ‘the guy’ came deliver the beer, Bailey asked him to thank Mike Hale, the owner. ‘The guy’ told Bailey that he just had, because Hale had done the delivery himself. According to Phil O’Brien, another Moisture Festival organizer and Hale’s Ales partner, “Mike came into the pub that first night and told us, ‘you have to see this thing! It’s like an Ed Sullivan show.” Some Hale’s folks went, and told others how much fun it had been, and more of them checked it out.

Still, “we lost our shirts,” daVis recalled, on that first show. Bailey and Neale suggested they hold a benefit show to make up the shortfall, and Hale’s offered the keg storage warehouse as a makeshift venue. “We would have some kind of party at Christmas for our people and vendors,” O’Brien explained, and the Moisture Fest Producers organized two nights – one for Hale’s and one for the public.

“It worked so well that Mike said, ‘why don’t you hold your festival here?’” Furst recalled, but O’Brien suggested, “or you said that.” In any event, Hale’s gave over the warehouse behind the brewery and pub for the Moisture Festival in 2004. “Hale’s is very generous that way. There is a big openness to arts groups in general,” O’Brien observed, and “as long as I’m here, it’ll be here.”

To Keep It Going

That first year at Hale’s, the warehouse was still active. The shows had cabaret seating, but ticket sales were so brisk that tables were being removed to put in enough seats to satisfy audiences. With volunteer help, the Producers built a stage, and each year they added to it with a backstage area, green rooms, restrooms for audiences and the box office. “After seven years,” Furst recalled, “the City said we needed a permanent permit.” They’d operated under a temporary, but the temporary-ness had worn thin.

Furst, who rarely performs now at Moisture, always gave generously of his time. In the first years, he booked the acts, kept the accounting books, arranged flights for performers, did lighting and, occasionally performed. “The volunteers have grown considerably,” he acknowledged, “I kept getting rid of jobs.” Today several people do jobs that originally only Furst managed.

In many ways, starting Moisture wasn’t the hard part. Keeping it going might have been, but the right people would come along. Rhonda Sable, who performed at the first few years of Moisture, had managed the Karamozov Brothers and Du Caniveaux troupes. “[Moisture Festival] had grown so quickly,” she observed, “it needed systems and procedures,” so in 2009, she created, and stepped into, the position of Director of Smooth Operations.

Current Smooth Operations Director Jen Wensrich came on to Moisture as a volunteer in 2006. Like so many volunteers, someone brought Wensrich to a show and she stuck. She eventually took over Smooth Operations in 2012, and recalled, with some reluctant fondness, “we had as many as five venues.” For Wensrich though, it is the volunteers that make it happen. “We have the most amazing family of volunteers,” she remarked, “we have a staff of 500 people, during the Festival.”

A Share System Of Distribution

“One thing that makes it possible,” Furst explained, “is the share system.” The payment the artists, and support staff (lighting, sound, photography, and rigging,) receive is unique to Moisture Festival. “Every performer gets a share of the pot, after the bills are paid and the overhead for next year is accounted for,” Furst said, “we are not having to negotiate 125 contracts,” for the performers, and “the Festival doesn’t run in a deficit if sponsors don’t appear.”

The share system means that performers don’t make as much as they would if they booked a gig, but Moisture Festival (again, due to volunteers – and sponsors) does provide transportation, housing, food and a per diem. “That we have more performers able to appear than can fit [in the Festival,]” observed Sable, “is a testament to the great thing we have here.”

Avner Eisenberg shared about a festival he started, in Maine, and how in the second year he heard “no end of complaining,” from everyone involved. He attended the Moisture Festival and found the difference startling, particularly the sense of community.

The share system also makes it possible to keep ticket prices low – an important objective of the Board of Directors and the Producers. “We wanted to keep ticket prices low so families can attend,” observed Randy Minkler, “and they will bring friends.”

“We are creating a community,” acknowledged Wensrich, “everybody comes together.” Iman Lizarazu spoke about how she is a solo performer, traveling alone from show to show. Moisture Festival gives her a chance to create connections. Here, her mentor, Avner The Eccentric, and other legendary performers share notes on her performances, and help her become more polished. “It’s quite magical,” she stated.

Charley Castors grew up in the circus, in Europe, as part of a family act. He’s since moved to the Pacific Northwest, where he teaches at SANCA, works with Teatro ZinZanni and serves on the Board of Moisture. “Here is a place of creation,” he said, “when I come here, I feel at home.”

More Moisture To Come

According to Martha Enson, one of the organizers of the Moisture Festival Burlesque Libertease, “if I think of my first moments, it is Ron Bailey, with a twinkle, saying ‘we’re going to do this thing. It’s going to be fun!” Certainly Moisture Festival owes a lot to Bailey, who is credited with founding the Festival – and naming it. However, as the April 2nd presentation proved, Moisture Festival is fourteen Board Members, five Producers, 500 volunteers, 2 ½ staff, 100+ performers and 1000s of audience members.

The presentation went on from there, with plenty more about Moisture. Produced by Alan Plotkin, it is part of a documentary being created from this panel discussion, one-on-one interviews and 10 years of previously recorded performances. Find out more about the documentary, and all things Moisture, by visiting the MoistureFestival.org website – and registering for the e-mail list.

Related Articles (By Date:)

- Moisture Under The Big Top

- by Kirby Lindsay, April 20, 2004, in the North Seattle Herald-Outlook

- Inviting Moisture To Stay

- by Kirby Lindsay, April 2005, for Fremont.com

- A Life Dedicated To Laughter (with Simon Neale)

- by Kirby Lindsay, March 22, 2006 in the North Seattle Herald-Outlook

- The Juggling Act (with Sandy Palmer)

- by Kirby Lindsay, March 21, 2007 in the North Seattle Herald-Outlook

- Love Among The Clowns

- by Kirby Lindsay, March 20, 2008 in the North Seattle Herald-Outlook

- Moisture Festival Development Gets Direction

- by Kirby Lindsay, October 7, 2009

- Why Volunteer For Moisture?

- by Kirby Lindsay, March 5, 2010

- Moisture Spreads Farther Afield

- by Kirby Lindsay, March 17, 2010

- Juggling With Moisture (with Tim Furst)

- by Kirby Lindsay, March 24, 2010

- Randy Minkler Answers Questions on Godfrey Daniels

- by Kirby Lindsay, March 18, 2011

- 10 Reasons To Attend Moisture Festival 2012

- by Kirby Lindsay, March 12, 2012

- Entertainers Strip & Soar At Moisture Festival

- by Kirby Lindsay, March 21, 2012

- Welcome A Second Generation Of Moisture Festival (with Ruby Joyce & Isak Moon)

- by Kirby Lindsay, March 23, 2012

- At Moisture Festival, Hammer Heads ‘Make Art Work’

- by Kirby Lindsay, March 20, 2013

- Don’t Miss The Magic Of Moisture Festival (with Louie Foxx & Joey Pipia)

- by Kirby Lindsay, March 24, 2013

- 10 Reasons To Attend The 10th Year Of Moisture

- by Kirby Lindsay, March 25, 2013

- Moisture Festival: Eleven Years & Counting

- by Kirby Lindsay, March 17, 2014

- Support The Moisture Fest Phenomenon

- by Kirby Lindsay, December 19, 2014

- Get Moisture For Trolloween (with Maque daVis)

- by Kirby Lindsay Laney, March 24, 2015

- Smooth Operations At Moisture Festival (with Jen Wensrich)

- by Kirby Lindsay Laney, March 24, 2015

- How Moisture Brings In The Clowns (with Hacki Ginda & Charley Castors)

- by Kirby Lindsay Laney, March 30, 2015

- Support A Million Laughs At Moisture Fest (with Cheryl Angle)

- by Kirby Lindsay Laney, February 27, 2016

- Moisture Festival Brings In Rob Mermin, To Educate, Enlighten & Entertain

- by Kirby Lindsay Laney, March 17, 2016

- Moisture Festival Presents Libertease, An Artful Dialogue (with Armitage Shanks)

- by Kirby Lindsay Laney, March 23, 2016

- A Stalwart Moisture Fest Volunteer Speaks (with Angela Parisi)

- by Kirby Lindsay Laney, April 5, 2016

- Isak Moon & A Moisture Festival Life

- by Kirby Lindsay Laney, March 16, 2017

- All In The Family: Presenting Famiglia Gentile!

- by Kirby Lindsay Laney, April 7, 2017

- Moisture Festival Volunteers: Some Random Experiences Required (with Mike Bailey)

- by Kirby Laney, March 15, 2018

- Rubbery Fish Make Play At Moisture Festival

- by Kirby Laney, March 28, 2018

©2021 Kirby S. Laney. This column is protected by intellectual property laws, including U.S. copyright laws. Reproduction, adaptation or distribution without permission is prohibited.